Why We Tell Stories

In Monday's chapel, I touched on why we tell stories. Here are a few paragraphs to whet your interest:

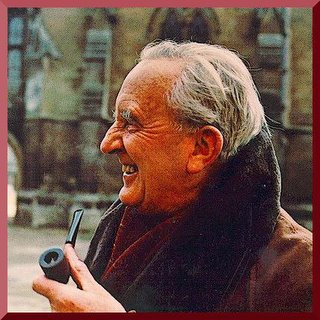

In a little essay entitled, “On Fairy-Stories,” the Roman Catholic scholar of Early English Language and Literature, J. R. R. Tolkien, suggests that stories awaken in us a desire for something beyond the known. He claims that true stories provide for us a fleeting glimpse of joy that partakes of an underlying reality or truth. That is, I would suggest, that stories are to some extent sacramental—they impart to us a certain nourishment which sustains us whether we are four or sixty-four. C. S. Lewis, Tolkien’s colleague who specialized in Medieval English Literature, says in his own essay, “On Stories,” that, “no book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty—except of course, books of information. The only imaginative works we ought to have grown out of are those which it would have been better not to have read at all,” (Essays in Honor of Charles Williams, 100). That is why Lewis can go on to say that, “an unliterary man may be defined as one who reads books once only,” (102).

Tolkien claims that the reason we tell stories in the first place is because we are made in the image of God: a peculiarly Christian thing to say. If God is by nature a creator and storyteller, because we have God’s DNA in our systems, we should expect to be storytellers as well. Stories serve to remind us of not only who we are, then, but whose we are. That is why Lewis was so vehement in his attack on movies, which he believed shut down and limited the human imagination. “Nothing can be more disastrous than the view that the cinema can and should replace written fiction,” he thundered. “The elements which film excludes are precisely those which give the untrained mind its only access to the imaginative world. There is death in the camera,” (102). One wanders what dear Jack would think of the current project to turn his vaunted children’s tales into Hollywood blockbusters! Lewis, Tolkien, and current writers like Frederick Buechner, believe strongly in this sacramental nature of storytelling—that stories which are true (not historically or factually, mind you, but true in terms of their truth content) have the ability to get at and shadow the Truth, with a capital T.

But I think that stories go beyond both Lewis’s and Tolkien’s Platonic and Augustinian categories. From the very first words we encounter in the Bible, the Hebrew Torah, we see God speaking and imposing an order on His creation. The very Hebrew word for that chaotic void—tohuwabohu—conveys verbally something of the disorder which opposes the Creator. The liturgical sameness of this creation story framing each day of creation in the same way, even suggests that its original context may well have been the sacred sanctuary of worship. For a people caught up in a world that appeared untrustworthy and spinning out of control, such a perspective is nothing less than a radical reorientation towards nature. Leaving the sanctuary or the temple, one would have emerged with the sense that words give to the world an order by which we can understand God, ourselves, and that world—all of which is impossible without the very gift of narrative which speech makes possible.

Fr. Walter Ong suggests just such a thing in his voluminous writings on Orality and Literacy. In the age of the ancient Hebrew prophets, the very speaking of a word from God brought terror to the most powerful and wealthy of kings. The language of the prophets conveys this fear as such messengers as Isaiah draw on the temple imagery of hot coals to suggest the burning nature of the Word of God. The prophets and the scribes which followed in their wake, came to understand that the words they spoke and wrote had enormous power to shake or to shape the communities to which they were sent.

<< Home